Pomona Island by Hayley Flynn

First published by Caught By the River.

I am on an island amongst only wilderness and ghosts; bricks and concrete. Waterways on two sides of the island run parallel to each other – the River Irwell to the North and the Bridgewater Canal in the South. Running through the island is the great brick spine of the railway bridge. At night this seems to loom closer. The island is not strictly an island.

Island: “A piece of land surrounded by water”, “A thing regarded as resembling an island, especially in being isolated, detached, or surrounded in some way”

Although it is not surrounded on all sides by water, by the latter definition it still qualifies by its isolation. People come here for nefarious reasons – like the people who come here to train stolen dogs for dogfights – but generally, people don’t come here. The island sits across three regional boroughs and is the confluence of railway, river, canal and road. It is the joining staple or the fold in the map. It connects many things but is not part of them. It’s surrounded by the city and is bound by obstacles, cut off from the world around it by its lack of signs and obvious access points. Isolated. Detached. Surrounded.

The sea which Pomona feeds into is many miles from here but the path beside the river has a distinct brackish quality and the air smells salty; seagulls perch on the twisted railings that seem to have been bent out of shape without explanation. The black iron rails bend and buck severely as if, after all these years, they have decided to mimic the crooked fingers of the blackberry bushes surrounding them.

Eventually the island tapers up river until it dissipates to nothing, becoming merely a path flanked by gargantuan hogweed: its great blooming poisonous heads each as large as my outspread arms. In the other direction it becomes even less than that, it peters out into a desire line across a steep ditch and that ditch abuts an empty road somewhere in the forgotten corners of Trafford. The bindweed is the only continuous trace of wilderness now, its seemingly perpetual white pillows spread like a rash right to the curb. The river and canals continue their paths out to the Mersey and back to the Irwell Spring.

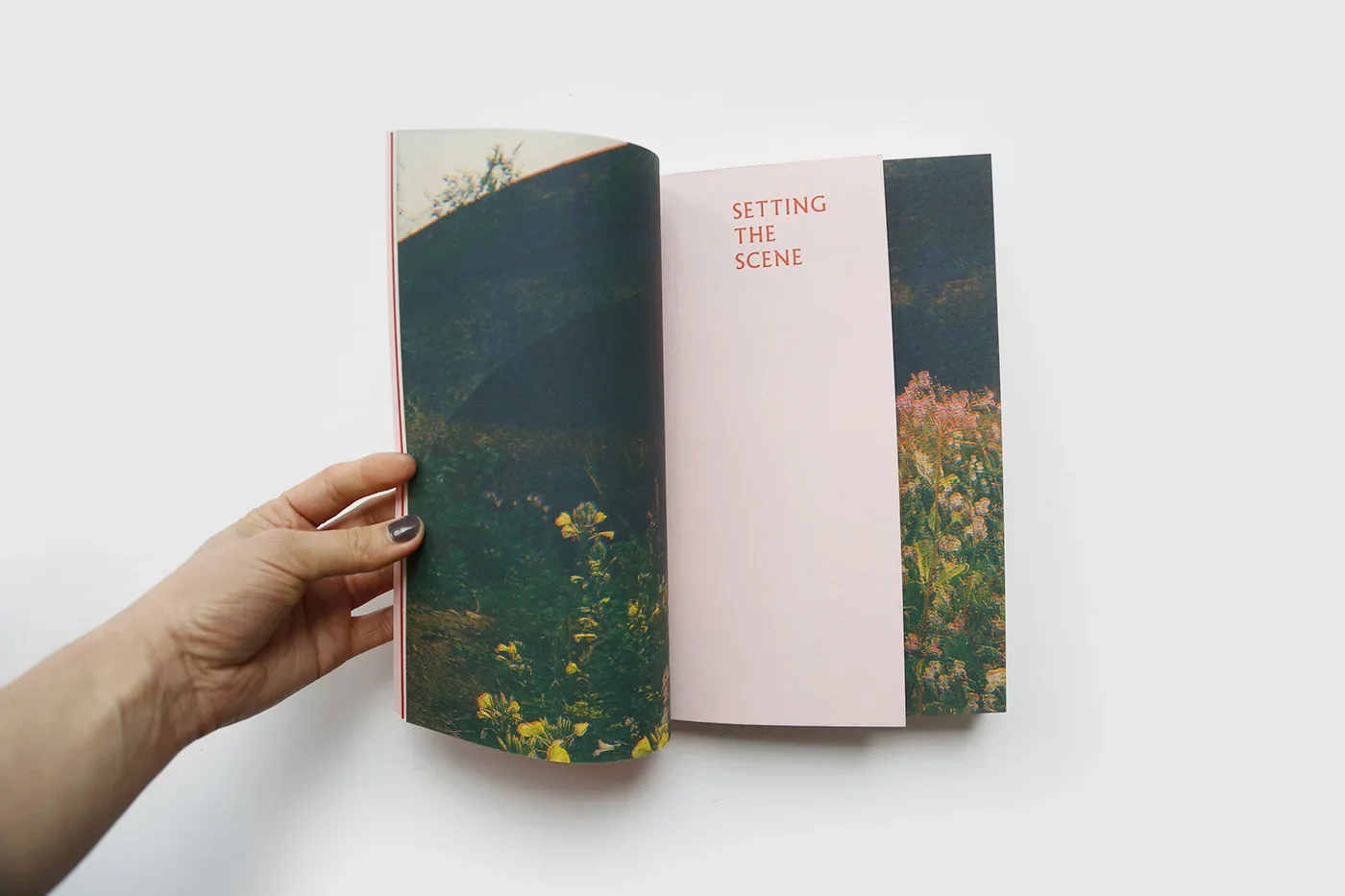

I am on an island. The moon above me is fat and yellow like clotted cream. Being almost winter all that remains of its bounty of wild flowers are the murky brown droops of decaying buddleia and the barren spines of blackberry bushes recently swollen with their own ripeness, now picked bare. The fireweed is wispy now – the long stems hold onto the feathery cotton seeds like plumes of smoke waiting to be blown out, or in this case, away. Their crimson fire tops have all been shed. Pomona, the goddess of fruit trees, hibernates.

As night approaches, the riverside streetlights that I expect to fire up at any moment remain cold and dark. A bird of prey drops a bloody seagull carcass on the path ahead of me. A graveyard of blue-grey snail shells crunch like bones beneath me. The night falls and darkness envelops everything. The island has become a black hole.

The cranes from the surrounding scrapyards screech and scream: “What made you think you could come to our island?”

One of many pieces about Pomona, more detailed articles I’ve written on it are published in various publications including The Guardian, and as the foreword (and photography) for Fruitful Futures.

Extracts of my work on Pomona have also featured with my accompanying photography throughout city centre buildings curated by Simon Bushell for Bruntwood’s digital art and film programme, and passages of this article have been turned into a public art panel on Pomona itself.

I also featured in the film Pomona Island (2014) by George Haydock.